Johnny & Virginia Soderberg

Choosing forever over fortune

Written by Liz Munsterteiger

Soderberg Trail Dixon Cove, Jeanie Sumrall-Ajero

When developers approached Johnny and Virginia Soderberg in the early 1980s, they were offering to buy the family's 2,100-acre ranch overlooking Horsetooth Reservoir—land Johnny's great-uncle Swan Johnson had homesteaded a century earlier. The plan was to subdivide it into 35-acre lots.

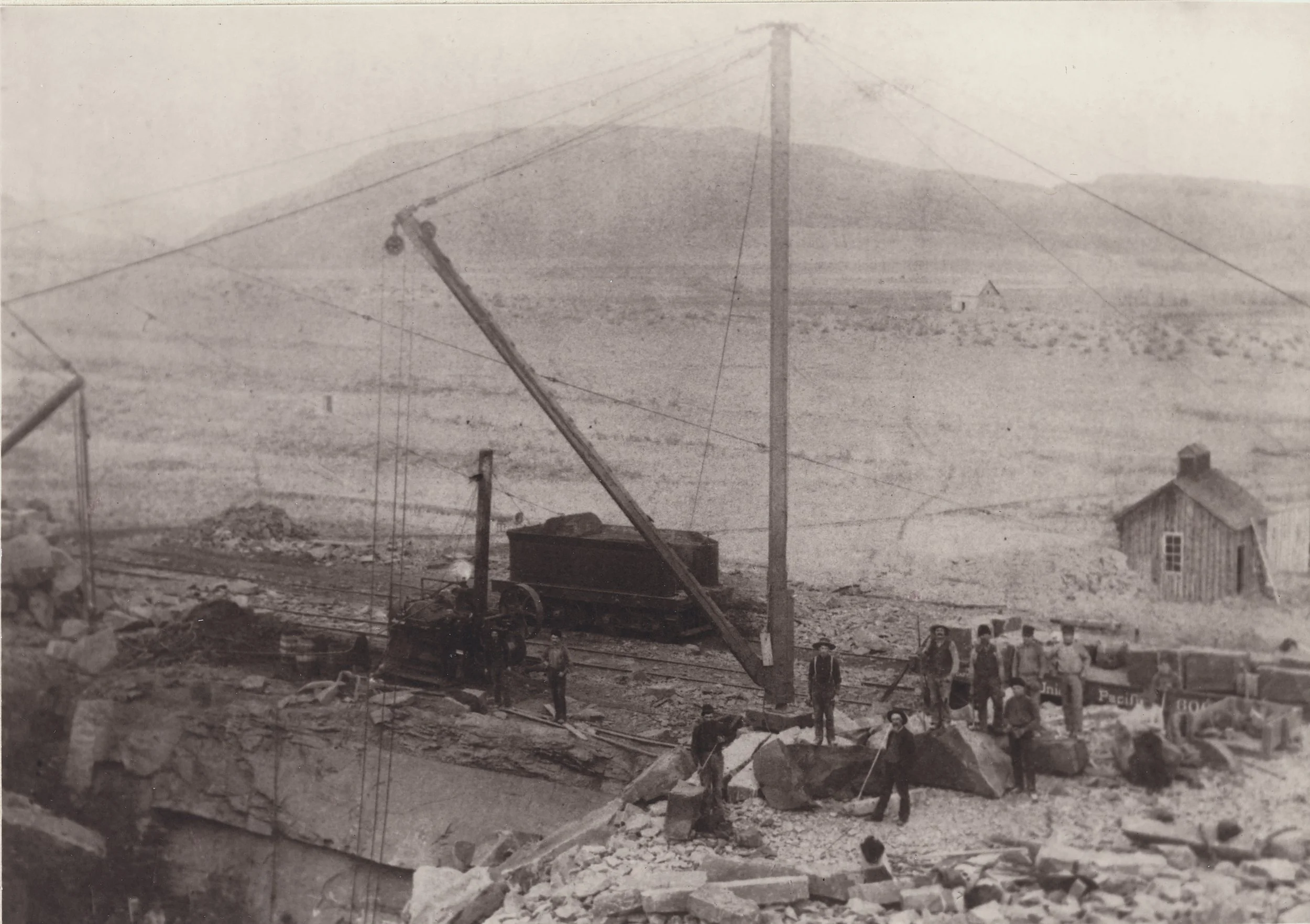

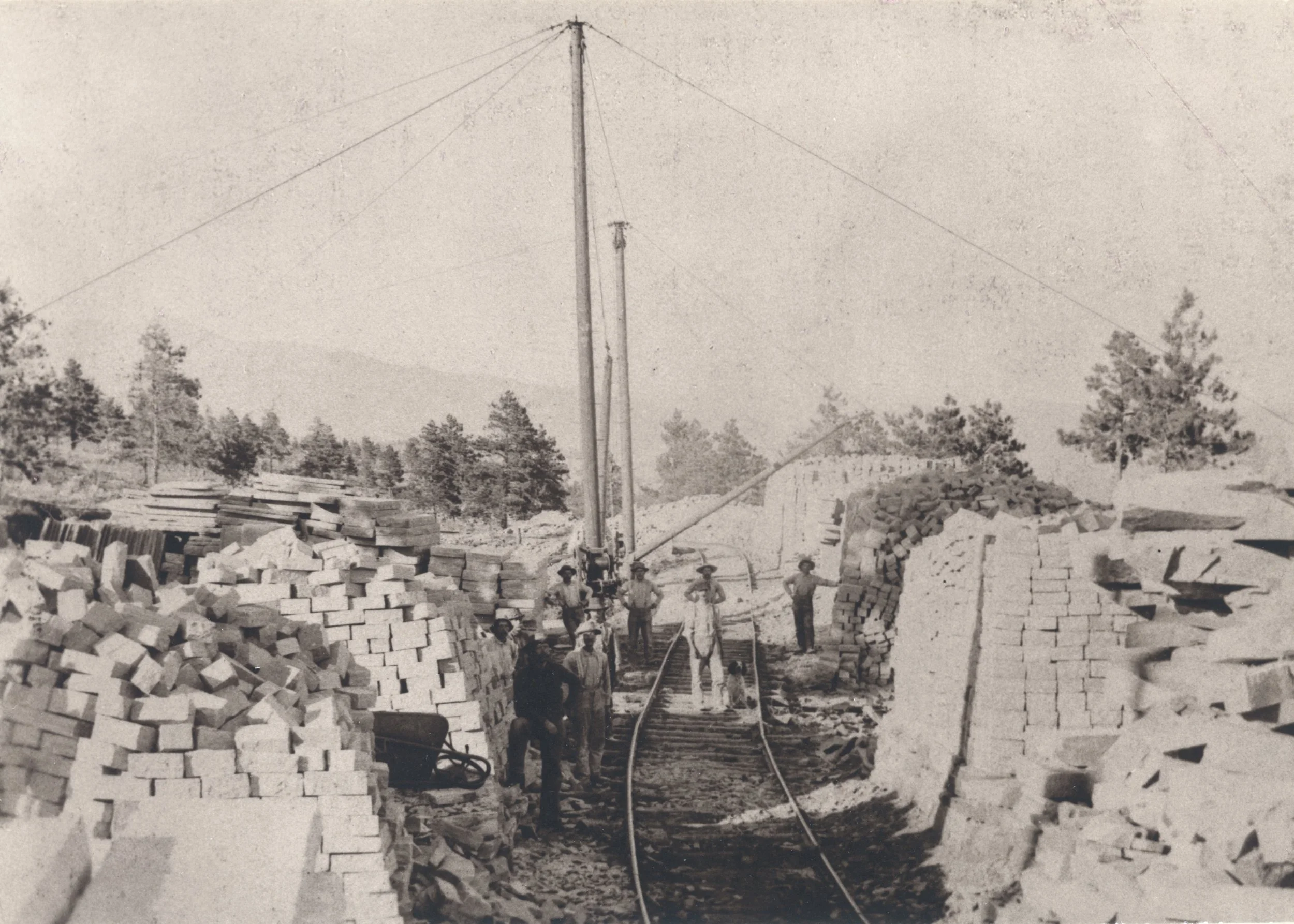

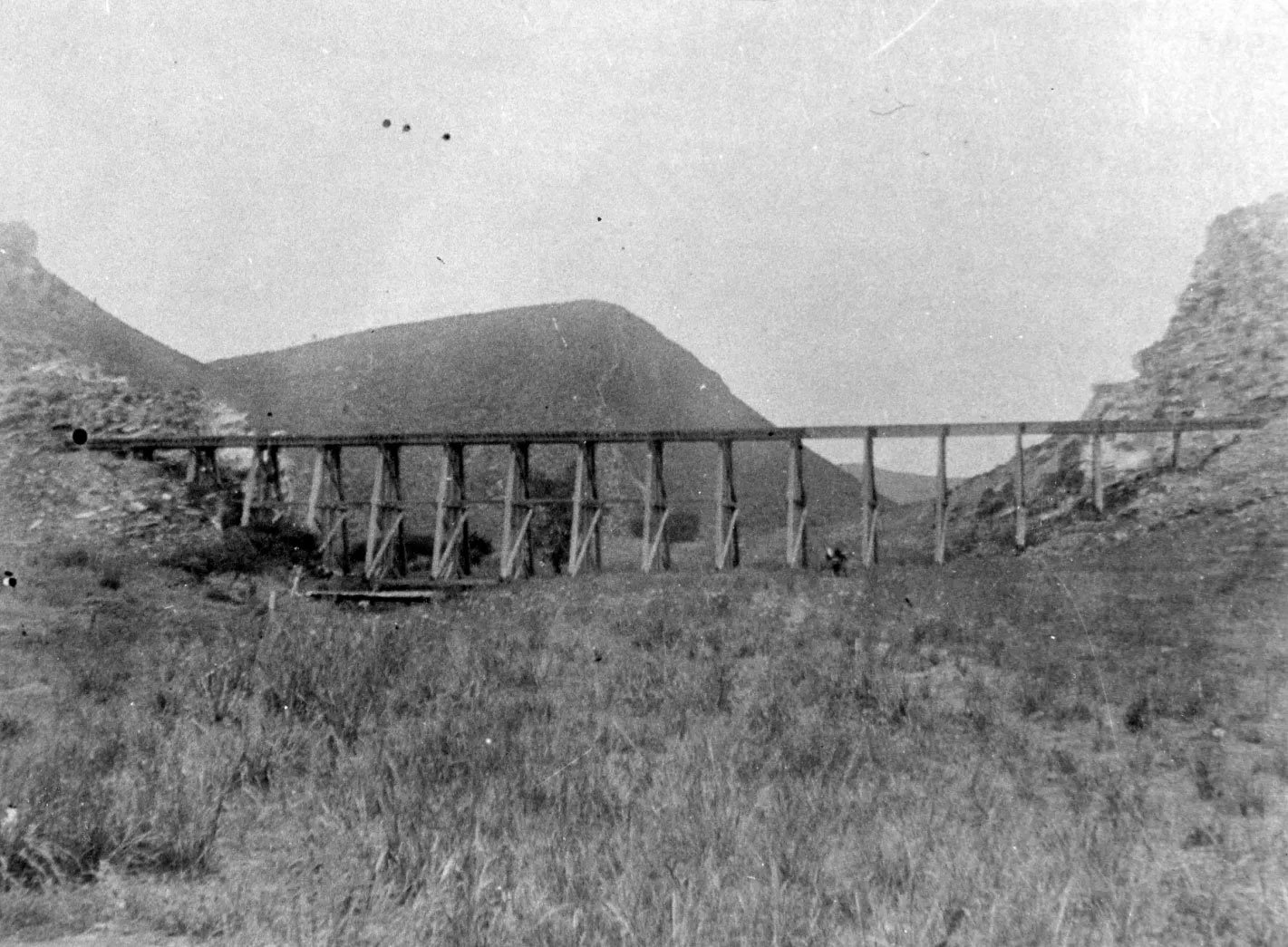

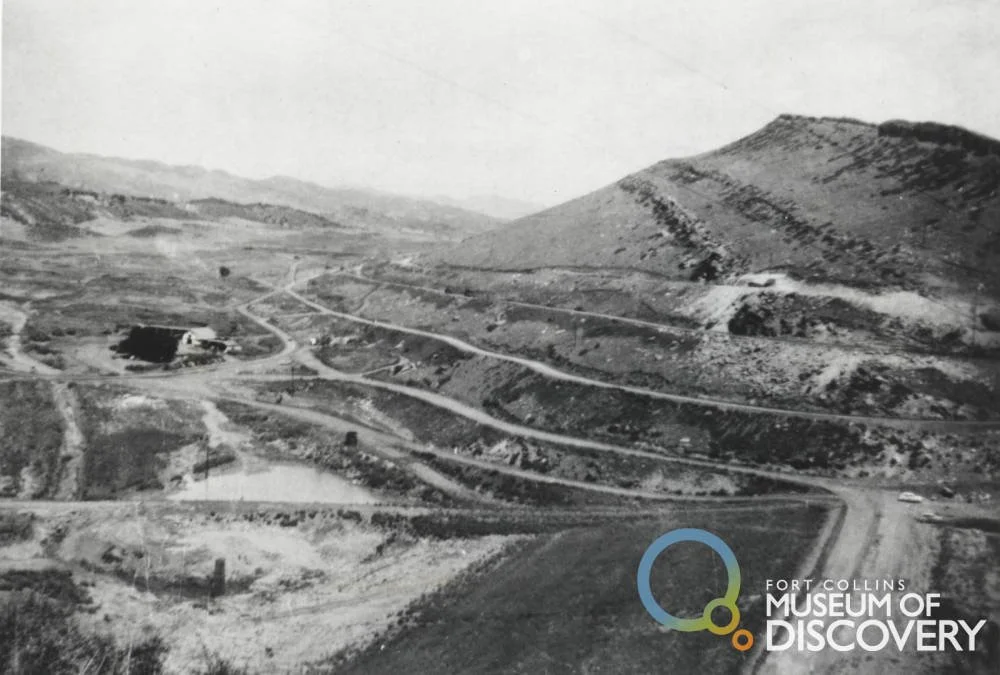

Johnny had already lived through one kind of loss. He'd grown up in Stout, a quarrying boom town that peaked at 900 residents in the 1880s before economic collapse and changing technology turned it into a ghost town. By 1947, when the Colorado-Big Thompson Project filled Horsetooth Reservoir, what remained of Stout—including land his family had owned for decades—disappeared beneath 156,000 acre-feet of water. Johnny was 35 years old when the reservoir swallowed the schoolhouse where he'd learned to read and the landscape that had shaped his childhood.

The town of Stout, 1885

Photo courtesy Fort Collins Museum of Discovery

Stout school children – entire school is pictured: Johnny Soderberg (10 yrs old) is in overalls in the 2nd row, 2nd from the right holding a straw hat); Korin Soderberg (2nd from the right in the back row) was the oldest Soderberg child; Ellen Soderberg (on crutches).

He couldn't save the town. But decades later, he would get the chance to save the mountain.

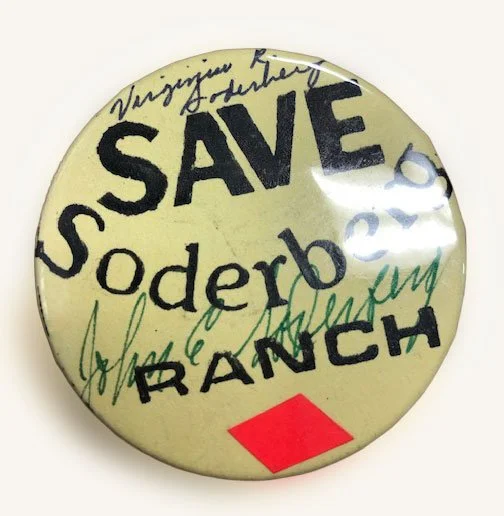

By 1980, Johnny and Virginia were preparing to sell to developers when citizens organized a campaign. They didn't want to lose the Soderberg ranch to subdivision and proposed extending an existing sales tax for an additional six-month for purposes of funding the land purchase as county open space. It passed.

Larimer County purchased 2,027 acres. Johnny and Virginia retained 114 acres around their homestead at 3909 Shoreline Road—the house built in 1889, the historic outbuildings, the five springs that still provided water for wildlife and livestock.

"We were going to subdivide it before that happened, and I'm glad we didn’t," Johnny said in a 1999 interview. "We wanted to see it in the park."

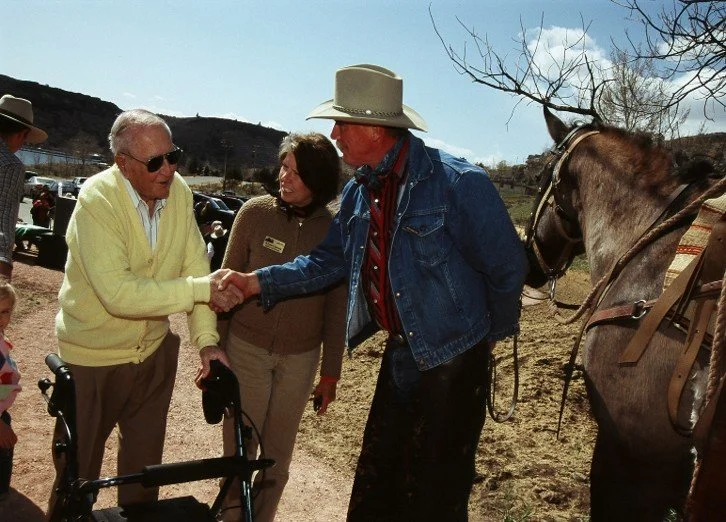

1999 Larimer County interview with Johnny and Virginia Soderberg

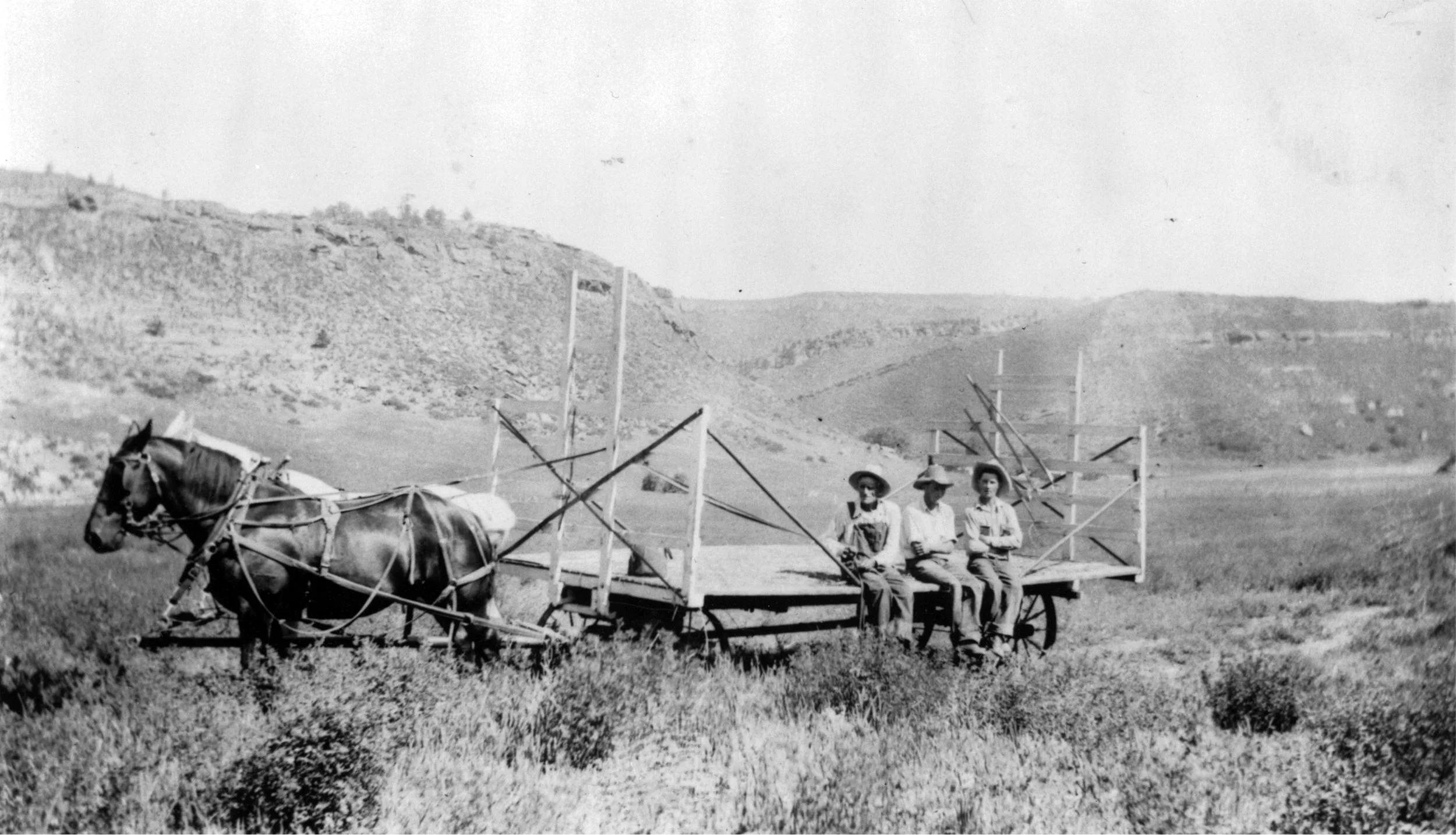

For Johnny, who had once said he felt "like a caged animal in a house," the decision reflected a lifetime lived outdoors. He'd worked the land since age 15, trapping furs, running a sawmill harvesting ponderosa pine from Horsetooth Mountain, and ranching. Virginia, who came from the Ozarks and married Johnny in 1980, enjoyed gardening and photographing the beauty of the landscape they called home.

A decade after the first sale, in 1998, Larimer County approached them again. Would they consider selling the remaining acreage? The Soderbergs could keep a 12.5-acre life estate—the house, the outbuildings, the immediate land around them—and live there for the rest of their lives. After they passed, everything would become public land, protected forever.

They said yes.

Swan Johnson trail, 2016, Brendan Bombaci

Johnny had one request: that a trail connecting the property to Horsetooth Mountain Open Space be named the Swan Johnson Trail, honoring the great-uncle who had first settled the land.

Today, that trail carries hikers and horseback riders through a landscape that was nearly lost to development. The Soderberg Homestead Trailhead provides access to Horsetooth Mountain Open Space with space for 20 vehicles and 10 horse trailers. Educational signs tell visitors about frontier ranching and the family who chose preservation over profit.

Most visitors don't know this mountain was nearly carved into house lots. They don't know one family's choice made the difference.

Johnny understood what it meant to lose a landscape to forces beyond his control. When he was given the chance to decide the mountain's future, he chose differently. Not because it was easy—he and Virginia faced real financial pressures—but because some things matter more than money. The mountain rises above it, wild and protected and open to all. Both serve the public good, but only one represents a choice the Soderbergs got to make.

Because they chose forever, generations will walk land that might have been subdivided and sold. They'll hike the Swan Johnson Trail without knowing Swan Johnson. They'll enjoy open space without understanding what it cost to preserve.

This landscape tells the full story:

Water and stone.

Loss and preservation.

What disappeared and what endures.

And what one family chose when given the chance to decide.

Johnny and Virginia Soderberg chose forever.

Because they did, the mountain remains accessible for all.

Visit the Soderberg Homestead

Sources: John Soderberg Interview (April 15, 1999); Resource Management Plan for the Soderberg Homestead Open Space, Larimer County (2003); Fort Collins Coloradoan (Jan. 18, 2022); Rocky Mountain Collegian (Nov. 14, 2021); Northern Colorado History blog (Oct. 16, 2015); Denver Public Library Western History Archive; Larimer County Department of Natural Resources.